The Case for Anticuration

We’re at a turning point in how we see the world around us. Are we ready to admit our viewfinders may be broken?

Hi. Hey. Hello. This is The Other 90, a blog about strategy from your friends at Quick Study. A recent client says that we “moved at light speed without compromising on research and quality,” and that “I’ll recommend them to anyone who wants to make their brand culturally relevant.”

If this is your first time, welcome! Feel free to check out the archive.

This piece is also being published on our website, where you can find out more about what Quick Study can do for your brand.

Let’s start here:

In the summer of 2011, the Midlands Arts Centre in Birmingham, UK, launched an exhibition called Anticurate. Its mission, according to those who organized it, was to “challenge the traditional hierarchies and practices of curating visual arts exhibitions.” In order to do that, they recruited groups of “anticurators” - people who specifically were not normal participants in the curation of the visual arts - to select the works that would be presented. To supplement the art on display, organizers Craig Ashley and Trevor Pitt also asked 60 arts professionals to tell them what the word “curate” meant in their eyes. The responses were printed on posters and displayed alongside the anticurated works. One professional compared curation to farming, another equated curating with caring, and a few got very literal with their definitions.

Three responses stood out to me when I read the PDF’d brochure from the exhibition:

The first, from Deidre Figueiredo, Director of Craftspace: “One or more people engaging in a creative activity to sift, sort and remix culture.”

The second, credited to “Juneau Project, artists”: “To curate is to engage in the process of making things visible to others.”

And the third, from Lorenzo Fusi, Director of Open Eye Gallery and Curator for Liverpool Biennial 2010 and 2012, is quite long, but this part feels most relevant to our conversation today: “In my opinion “anticurating” is strategy practiced every day, in every part of the world, including by those who are conventionally labelled or addressed to as “curators”. These cultural operators, committed as they were to deconstruct the relatively recent “tradition” of the discipline, act similarly to the artists: they attempt to find their own voice, keeping in mind the past so to move always a little forward…”

It’s worth noting, as Fusi alluded to, that the act of assembling a bunch of non-curators in order to choose art for an exhibition is in itself an act of curation; that at its broadest definition, just about any actions we take on a daily basis are in a sense a curation as well. We are all sifting, sorting and remixing culture on a daily basis, whether we think about it or not.

But are we curating as a means of making things visible to others, as the Juneau Project definition states? Kyle Chayka would say not so much. In a recent post from his Substack, Chayka posits that the majority of curation today is not meant for others, but actually for ourselves: “...curation is not really curation if it is solely directed at projecting an image of the self. Then it’s just narcissism. Curators, in the context of 20th-century art museums, are meant to care more about the objects at hand than their own taste. Lately it feels like the opposite: Showing off personal taste is the endpoint. We have too much curation, and not enough of it well-curated.”

Part of the issue if you ask Ted Gioia is that there’s just too much stuff to sift through to get to curation in the first place. In his recent “State of the Culture” breakdown, Giola cites the extreme abundance of stuff we have at our fingertips to consume in pop culture - from books to videos to podcasts - before pointing to the larger problem in his eyes: “Never before has so much culture been available to so many at such little cost,” he says. “There’s just one tiny problem. Where’s the audience?”

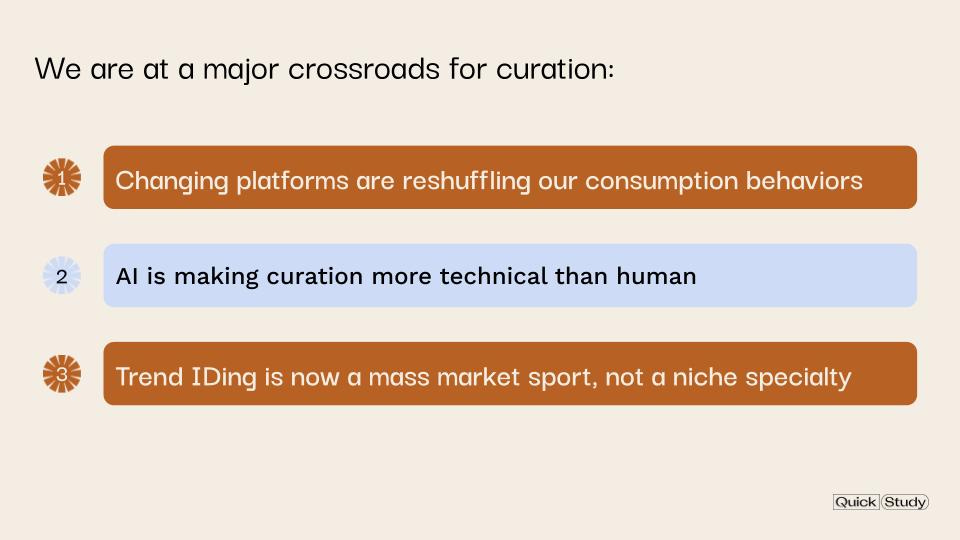

A lot has changed since the Anticurate exhibition in 2011, or even since Ana Andjelic called curators the new influencers in March 2020. We are currently standing at a major crossroads for curation that could impact how we take the world in and sort through it all for the foreseeable future.

First, our platforms are changing. TikTok has arguably become the biggest curator of culture in the United States over the past three years, both in how we’ve curated our own follows but also in how frequently the algorithm has been hailed for its curatorial prowess, showing us content we didn’t even know we would love, relate to, or become obsessed with. Now, we are rapidly moving toward the possibility of a TikTok-less future, one that would instantly create a gap in the curated consumption of over 150 million Americans. (One may argue that other platforms will pick up the slack, but that ignores the fact that no other platform has been able to even come close to a viable competitor yet.) On top of that, Twitter’s continued … Muskiness? … means its place of power as a curated instant feed has become the subject of algorithmic tweaks and general ugliness. Even if the platform remains, it has lost cache and many users who were once the trusted curators of the feed for others. And again, a true viable alternative has yet to be identified, and likely won’t be.

Second, there’s the explosion of AI, where myriad curation possibilities abound. AI tools could potentially curate our lives in increasingly powerful ways with an efficiency that humans cannot compete with. We’ve already been served AI as a curator in so many ways (take Spotify’s auto-created playlists for example) but there was a certain amount of passiveness to that AI that made it feel less obvious. Now it seems like we are seeing new AI potential by the hour, and often it’s being used in ways that either assist in someone’s curation or does all of the curation for us. Regardless of how accurate or ethical that curation is (and we’ve seen many examples of how inaccurate and unethical these new technologies could be), it’s a game changer that will lead to many new curation-based services in the near future, all vying to become the curator of likely already curated information.

Third is that we’re living during the gold rush of trend hunting. I’ve written about this a little before, and others have ad nauseam, but it’s worth mentioning that creating a cultural language around trends has also forced everyone into a game of immediately defining what it is they are doing and how it fits into the broader contextual narrative of the world. Nothing can just be anymore, it has to fit a jigsaw puzzle. As a strategist by trade, I love fitting seemingly disparate pieces of information and cultural signals into neat little boxes, but I also have learned over the years how to know when the pieces don’t fit. To the mass trend curators and definers of this moment, the culling doesn’t matter; it’s just trends all the way down, the more the merrier, the person who names the most the winner. It’s about as self-aware as curation has ever been, and speaks directly to Chayka’s point about curation becoming more about personal taste than anything useful for others.

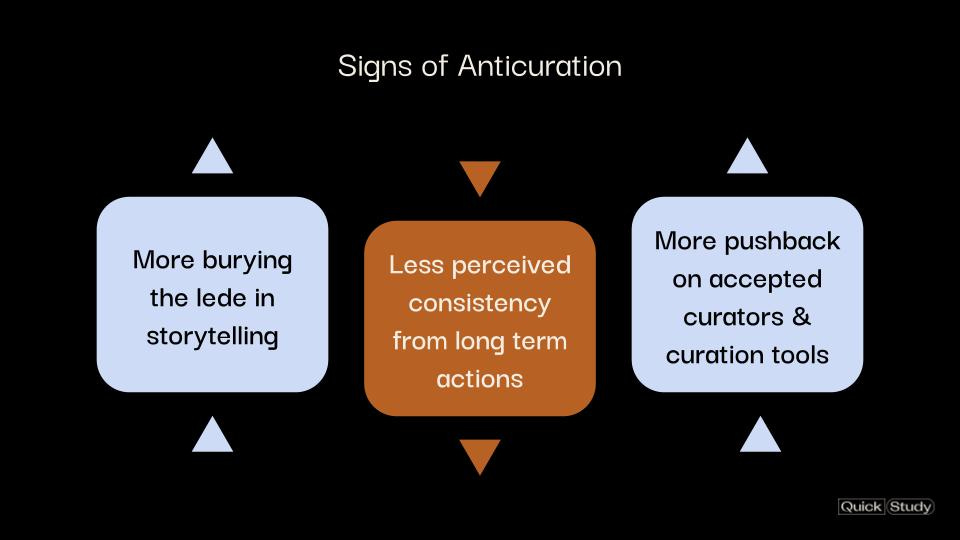

Those 3 “trending topics'' - and many others - are what led me to think about the recent history of anticuration. With so much changing in terms of how what we see is determined and disseminated, are there also cracks forming around how we express what we’ve consumed? Might there be some signals emerging around how folks are pushing back on both the idea of curation and the expectations that have come to be formed around how we curate?

For example, when photo dumps became a trend on Instagram, much was made about how they were a signal of people wanting more authenticity in their feeds and their lives. Looking back on it now, and recognizing its staying power, I think it’s interesting to reframe photo dumps as an act of anticuration. Sure, the images in the carousel are still “curated” in a literal sense, but the idea of burying the headline (an engagement, new house, big vacation) amidst a flurry of seemingly random pieces of content is certainly a fuck you to the manicured feed of years past.

Similarly, the Corecore trend is its own act of anticuration. Playing off the incessant trend IDing we discussed earlier that was particularly rampant when it came to naming “-cores” on TikTok in 2022, Corecore came to both mock and evolve the core aesthetics of TikTok with “stylized video edits and meme compilations of glitzy, moldy and deep-fried shitpost videos akin to schizoposting and Gen Z signifiers.” It is, to paraphrase Fusi from earlier, people doing curation of a specific type so as to act against curation.

This anticuration attitude is also not dissimilar from the deinfluencing we are seeing in the creator space. Originally an explicit non-endorsement of products by unimpressed influencers, it quickly became - like so many other trends - a mishmash of content that essentially influences in its own way. Deinfluencing, even if it is about calling out products for not being worth it, is still influencing, but done as anticuration. With so much content about what the right answers are, or pushing people toward life hacks, easy solutions, etc, the novel thing became to call out the negatives and the ineffective.

So where is this need for anticuration coming from right now? Quite simply, the way the world is curated today doesn’t work for most young people. In a time when the “norm” has become crisis, young people in particular are fatigued. Consider the last 7 Oxford Dictionary words of the year and think about what it’d be like to grow up in the shadow of their meanings:

2016: post-truth

2017: youthquake

2018: toxic

2019: climate emergency

2020: n/a (no word chosen because 2020 was that bad a year they couldn’t decide on one)

2021: vax

2022: goblin mode

It’s no wonder that over the last year, Gen Z has shown increasing apathy for the world around them. According to GlobalWebIndex, between Q1 2021 and Q3 2022, Gen Z globally became less interested in what’s going on in the world, less interested in environmental issues, and less interested in current affairs. 29% are prone to anxiety, and only 31% are comfortable talking about their mental health (lower than all other generations).

In moments of respite between crises, there isn’t much to get excited about, either. To many, curation has made the world boring. In a widely shared piece at the end of 2022, n+1 asked us to consider why everything is so ugly: “We live in undeniably ugly times. Architecture, industrial design, cinematography, probiotic soda branding — many of the defining features of the visual field aren’t sending their best.”

Around the same time, Blackbird Spyplane coined this the “Era of Mids”, stating “‘we can and should do better,’ as a culture, than settle for swagless, characterless, joyless, mass-market mids.”

Culture has taught us to organize everything, but when everything is sad, curating it all makes it feel even worse. Throw in a dollop of dull and you’ve got a cocktail for some truly uninspiring curated lives. Or put another way, a ripe space for some counter mentality.

Anticuration fills that space with reminders that looking beyond the curated can be the refreshing respite that’s missing. In Spike Art Magazine, Dean Kissick summed it up thusly: “We’re told every morning that life is miserable and hideous, which it’s not, and also that culture is high-quality and life-affirming, which is plainly ridiculous. This is breathtakingly diabolical because the opposite is true: life is still beautiful, it’s culture that’s in the doldrums.” In that sense, anticuration is a push against the way our lives are curated currently and what that curation tells us about the world. It’s a - dare I say - optimistic approach, one that opts for more surprise, more fun, and more randomness to help break up the patterns in search of newness.

I should be clear that I’m not saying brands specifically should strive to become known as anticurators, but there is certainly an argument to be made for the fact that the novelty of your story and how you tell it is more important than ever, especially if it bucks the norm in a truly authentic way. Our industry talked for years about making “thumb-stopping” and “snackable” content, and then proceeded to mostly make things that looked like what everyone else was doing. In a moment with so much change from platforms, consumers, and the world around us, there’s never been a better time to experiment with a little anticuration of your own. Maybe it’s a test & learn, maybe it’s a one-off campaign, maybe it’s just a more honest tone of voice; regardless, the time is now to approach things differently than ever before.

Amy Pettifer, a visual arts consultant and writer, was one of the 60 who provided a definition of curate to the Anticurate exhibition in 2011. As part of her response, she acknowledged that the vagueness of curation makes it the perfect cover for a variety of activities, something we’ve only seen grow over the last 12 years: “Curate is a word that really doesn’t have an empirical meaning (it is underlined in green in my grammar check) and as such it can tend to find itself in some odd places. Places where perhaps it doesn’t belong.” She went on to say, “Perhaps it is this lack of definite meaning that makes it so appealing; the fact that you can claim it without having to justify it, a creative act in itself perhaps.”

We are now at an interesting moment where our world is increasingly curated not through creative acts but through technological ones, and that distinction will become even more important as AI continues to infiltrate our actions on a daily basis. That tension is what makes acting out against curation so interesting - are we acting against technology? Other humans? Both? Anticuration could be automated in theory just as curation is (StumbleUpon, for example, was an anticurated technology experience powered by human submissions), so who really is the enemy of this anti? To me, the enemy is the expected, the conformist, and anything that feels known. Anticuration is sort of a reality check for ourselves, and good anticuration should feel like the “Hold on, you’ve been scrolling for way too long” wellness checks on TikTok that shake you out of the doldrums and give you a chance to escape to somewhere new.

Later on in Pettifer’s definition of curate she says that “[curating] means noticing. It means making a world ... albeit a temporary one…” This is likely the best way to look at how anticuration can be applied to brands and creators. Going against the accepted, making space for the opposite, builds a world that is different from the dull, crisis-ridden one we see most often. It paints a different picture that feels a lot more interesting and a lot less feed driven. It doesn’t have to be part of a massive world-building exercise - quite the contrary; the outlier-ness of your action is what will make it true to the anticuration mentality. We can all be part of the anti-dote so many others are looking for if we just resist the urge to conform a little bit harder.

The Other 90 is written by me, Rob Engelsman, a former baby model and now Cofounder & Strategy Partner at Quick Study. To find out more about how we help brands and agencies get to smarter plans faster, email rob@quick.study. You can also find me on Twitter (for now), Instagram, & LinkedIn.